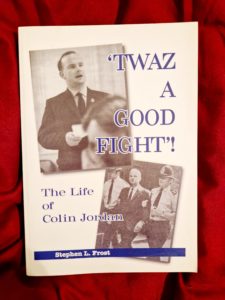

’Twaz a Good Fight! The Life of Colin Jordan by Stephen L. Frost, MA. N.S. Press, P.O. Box 6, WF16 OXF, West Yorkshire, Heckmondwike, UK. Published 2014. Trade paperback, 336 pp., 28 photographs, appendix.

The following is an expanded version of a review that appears in the May-June, 2015, issue of Heritage and Destiny.

WITHOUT A DOUBT, Colin Jordan (pictured) was one of the foremost White racial dissidents in the United Kingdom during the second half of the 20th century. Beyond that, he was an eloquent and forthright spokesman for National-Socialism, which is certainly the most hated and misrepresented creed of our times. Although his reputation as a fighter for his folk is well established in Great Britain, he is almost unknown elsewhere. I have frequently described him to my fellow Americans as “the British George Lincoln Rockwell.” He was that, in a sense, but he was also much more: whereas Rockwell’s public political career lasted a scant eight years, Jordan’s spanned some five decades, from the 1950s through to the first decade of the new millennium.

’Twaz a Good Fight! is the first full length biography of Jordan to appear. It is written by Stephen Frost, who currently leads the British Movement, which Jordan himself founded. In addition to interviewing Jordan on numerous occasions, Frost was given free access to Jordan’s voluminous personal archives. He further incorporates into his text fragments from Jordan’s unfinished autobiography, Before the Sun Goes Down. The result is a detailed and sympathetic account of the life of this extraordinary personality.

Frost begins at the beginning: “John Colin Campbell Jordan was born in Birmingham, on the 19th of June, 1923, the only child of Percy and Bertha Jordan.” He enjoyed a comfortable and unexceptional middle-class childhood. The only unusual feature of his early years was an extended visit to Germany in 1937, where, at age 14, was able to witness and experience Hitler’s Germany first hand. The journey made a profound impact on the intelligent and sensitive adolescent that would have huge ramifications later in his life.

Jordan attended the prestigious Warwick School, where he received a first-class education. He graduated in 1942, at age 18, in the midst of the Second World War. He had already begun his political awakening by that time, but nonetheless, as a patriotic Englishman, he felt it was his duty to serve his country in its time of need, and he enlisted in the Fleet Air Arm. In due course, he was transferred to the Royal Air Force. Jordan was uncomfortable about his country’s war with Germany, and he publicly stated his belief that the war should end by way of a negotiated settlement. This resulted in another transfer, this time to the Royal Army Medical Corps, a non-combat section in which he served the rest of his enlistment.

Upon his demobilisation in 1946, he began studies at Cambridge University where he studied history. He graduated with honors in 1949, and began a career in teaching. But his real interest — his primary career — was not in education, but in politics. Jordan’s lifelong political involvement may be divided into four periods: his political apprenticeship, the National Socialist Movement, the British Movement, and Gothic Ripples.

His first involvement was in the British People’s Party, led by the Duke of Bedford. Later he formed the Birmingham Nationalist Club. Following that, he was an active member of A.K. Chesteron’s League of Empire Loyalists, in which he learned the art of extra-parliamentary political activism. It was also during the early 1950s that he first made contact with the famous pre-war British National-Socialist Arnold Leese.

Leese, an elderly man by then, limited his political involvement to publishing the newsletter Gothic Ripples. He was impressed with the brilliance, passion and dedication of the young Jordan, and supported him morally and financially. Indeed, Leese financed the publication of Jordan’s 1955 book, Fraudulent Conversion. In 1958, following Leese’s death, Jordan recieved as a bequest from him a building on Princedale Road in London. Henceforth known as the “Arnold Leese House,” it became the headquarters of successive organizations which Jordan founded or joined. It gave him a stable physical base of operations, which proved to be invaluable in the struggle ahead.

The first of these organizations was the White Defence League (WDL). In 1960, the WDL merged with a number of other groups to form the first incarnation of the British National Party (BNP). The BNP included within its ranks both moderate racial nationalists and a smaller number of hardline National-Socialists. Jordan was the leader of the NS contingent. The two factions did not always get along together, and as time went on the BNP was increasingly riven with internal disputes.

Finally, in 1962, Jordan led his fellow NS loyalists out of the BNP and formed the National Socialist Movement. Biographer Frost devotes three lengthy chapters to the NSM and its activities. Thanks to his access to Colin Jordan himself and to Jordan’s archives, Frost is able to chronicle the saga of the NSM in extreme detail. He sets right erroneous impressions that have been fostered over the years by Jordan’s numerous and powerful enemies.

Among the episodes Frost discusses are the famous Trafalgar Square rally of April, 1962; the foundation of the World Union of National Socialists by Jordan and Rockwell in that same year; the “Spearhead” trial and Jordan’s subsequent conviction and imprisonment; Jordan’s tumultuous marriage to the French fashion heiress Francoise Dior; and his second imprisonment, in 1967, for violating the Race Relations Act. (Specifically, he was found guilty of violating said act by printing a leaflet entitled “The Coloured Invasion,” which warned Britons about the dangers of massive non-White immigration.)

But this brief summary does not do justice to Frost’s account of the countless small-scale activities that Jordan and the NSM undertook. On one occasion, Jordan disrupted the proceedings in the House of Commons, where a measure to betray the White people of Rhodesia was being proposed.

As the debate got underway, officially, the Second Reading of the Southern Rhodesia Bill, the Commons statement by the Conservative MP for Cheadle was suddenly interrupted as Colin Jordan jumped to his feet, casting off his disguise he shouted loudly, “The National Socialist Movement stands for independence for Rhodesia. Do not impose sanctions on the white people. Wilson is betraying the interests of our race in Britain by colored immigration! (p. 182)

Although he was led away by police officers, he was rewarded for his impudence with front page news coverage in The Sun.

But such activities did not always end so calmly. In January, 1962, Jordan and the NSM disrupted an election meeting of Patrick Gordon-Walker, whom Jordan considered to be an especially odious example of a race-betraying White politician. On that occasion, Jordan was viciously attacked by some 20 members of the Jewish ’62 Group’ when he tried to speak.

Cries of “Kill him! Kill him!” were clearly heard over the shouting and noise in the hall. One of the ’62 Group’ heavies grabbed Jordan from behind and was trying to choke him as other ’62 Group’ stewards punched and kicked the helpless NSM leader. Fortunately for Colin, the police intervened and escorted him from the building, blood streaming from his nose, mouth and a cut on his forehead… Despite the beating and throttling, Jordan felt satisfied that he had not only gained maximum press coverage for himself and the NSM, but had disrupted the Labour Party meeting, had humiliated the hated Labour Party candidate, and had exposed the criminal, violent nature of the ’62 Group’ in front of the national and international news media. (pp. 172-173)

Upon his release from prison in 1968, Jordan dissolved the NSM and reorganized it as the British Movement. The British Movement was similar to the NSM in many significant respects, but differed from it in that it was not a forthrightly National-Socialist organization, and, unlike the NSM, the British Movement stood candidates for public office on occasion. The British Movement was a rival of sorts to the National Front (NF), which past a certain point was led by Jordan’s former NSM colleagues John Tyndall and Martin Webster. On the whole, the British Movement was a smaller, more tightly-organized and more militant racial nationalist formation than the NF, which in the 1970s looked as though it might make a major breakthrough and become a serious force in UK politics.

But although in its outward appearance the British Movement seemed to distance itself from the open National-Socialist approach of the NSM, its ideology was essentially the same. Frost gives this example of how little the British Movement had strayed from the NSM:

In 1971, keen to appear as a developing organisation, British Movement had begun using the American slogan, ‘White Power’. Colin Jordan had tentatively introduced the slogan into articles in his bulletin British Tidings in the Autumn month issues of the previous year, and in February 1971 began to publish stickers, posters, and other BM literature bearing the caption “White Power for a White Britain” and variations of the same. Jordan knew that the National Front leadership was wary of using the slogan because of its origins with George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party, so in the hope that he could steal ahead of the NF and attract a younger following, Jordan presented the new BM slogan as, “White Power — the white man’s power which made this country, and the power represented by the British Movement, to restore this country to the white people to whom it rightfully belongs.” (p. 236)

The British Movement soldiered on, but never escaped living in the shadow of the larger NF. In 1975, citing personal circumstances and health, Jordan turned the leadership of the British Movement over to Michael McLaughlin. Although the transition from one leader to another went smoothly at first, it was not long before the two men were at loggerheads with each other.

In 1979, Jordan began issuing a small, typewritten NS newsletter. He named it Gothic Ripples, as a tribute of sorts to his former ideological mentor. This became became his primary Movement activity for the rest of his life. At this point he was effectively in political retirement, although he never fully stopped his involvement in NS and nationalist affairs. On into the new millennium, he was still serving as a guide and mentor to new generations of racial activists, both in the UK and abroad.

When he was leading the WDL, NSM and British Movement, Jordan was in a position to determine the standards and quality of the members and activists of these organizations. Once he had relegated himself to an advisory position, however, he no longer had this control. One example of his frustration at the lowering of these standards is shown by an episode during the campaign to defend Robert Relf. Relf was a longtime Jordan supporter who had provoked the ire of the established authorities by placing a small sign in front of his home reading, “For sale to an English familiy.” He was subsequently jailed for violation of the Race Relations Act. Jordan was in the forefront of Relf’s defense campaign. On March 4, 1979, Jordan helped to organize a demonstration in support of Relf outside Winchester Prison. All did not go as Jordan had hoped. Frost writes,

One aspect of the protests outside Winchester Prison caused Colin Jordan a degree of disapproval; amongst those supporting the ‘Free Robert Relf’ march were several coach loads of NF supporters bussed in from London, and during the course of the day many of them were drinking heavily in the pubs around the area with the obvious consequences…[T]he sight and sound of numerous drunken young men supposedly present to support Bob Relf angered him. He had hoped for a solid and serious body of support for the protest, but the sight of stacks of empty beer cans around the rally site undermined the honourable nature of the day for Colin Jordan. (pp. 279-280)

Incidents such as this caused Jordan to rethink his previous commitment to mass action and electioneering as a strategy for advancing the Movement. In 1986, he authored an essay entitled, “Party Time Has Ended: The Case for Politics Beyond the Party.” In this and subsequent writings, he argued for a form of political guerrilla war to be waged by an elite “task force” in place of traditional political campaigning. In a sense, he was returning to his roots as a League of Empire Loyalists activist.

The scope of Jordan’s life as Britian’s premier racial dissident is truly breathtaking, and Frost does a masterful job in providing a framework that lists Jordan’s involvement in the Movement month-by-month, week-by-week — and sometimes day-by-day! However, lost in all the details about this meeting and that demonstration, etc., is a broader overview of Jordan’s ideas. For Colin Jordan was not just an outstanding and tireless racial activist, he was also a thinker and ideologist of the first order. There can be no doubt that Jordan, as Frost accurately portrays him, was concerned about the perils of non-White immigration into the UK. But Jordan was more than just an anti-immigration campaigner: he was a committed National-Socialist who felt that the NS “world creed” (as Jordan termed it), held the ultimate answers for all of the problems facing the native population of Britain. No biography of Jordan can be considered as truly complete unless it discusses his ideas and their evolution, and not just his activism in trying to put those ideas into effect.

I would also be remiss if I did not mention some production problems with this first edition of ’Twaz a Good Fight! The book is in serious need of a thorough proofreading. There are numerous typographical, grammatical and spelling errors, all of which distract from the author’s narrative. One hopes that these can be combed out of the text in future editions.

And there will be future editions, because ’Twaz a Good Fight! is destined to be a classic in the library of Movement literature. It is a shame that Colin Jordan never finished his autobiography, but this book is the next best thing.

(Source)