See also Murder at Spandau by Colin Jordan (1989) and Smashing the Peace Stone by Colin Jordan (1999)

The Story of a Man Who Made More Sacrifices for World Peace in Our Century Than the Rest of Mankind Put Together, As Told by Colin Jordan

The Story of a Man Who Made More Sacrifices for World Peace in Our Century Than the Rest of Mankind Put Together, As Told by Colin Jordan

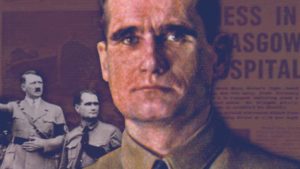

THE PLANE sought refuge from its pursuers in the evening haze – for it was German, they were British, the date was 10 May 1941 and the war was 1½ years old. Escaping the two Spitfires, the Messerschmitt 110 continued its 900-mile flight, crossing the Northumberland coast, dipping dangerously low over fields and villages to avoid detection, its fuel, barely enough for the one-way trip, dwindling alarmingly. Entering Scotland and reaching the vicinity of its objective, the home of the Duke of Hamilton, the plane’s pilot, all alone, made in the darkness his very first parachute descent.

The man was the Deputy Leader of Germany, Rudolf Hess. He had risked his life and staked his freedom in a feat of flying which Luftwaffe expert Colonel Udet had told Hitler was impossible. He did it, not to wreak some special destruction on Britain, but to bring peace between two brother nations who, together in alliance, could have assured the security and prosperity of the white peoples of this globe for many generations to come. History holds few, if any, more momentous occasions or more daring acts of benevolence. No-one deserves the Nobel Peace Prize more than this man.

Anglo-German accord within a European settlement had been the bedrock of belief with both Hitler and Hess throughout their political lives. Both were appalled when Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, on the spurious pretext of an agreement to defend Poland against wholly ‘unjustifiable German demands’ for the return of German territory. This pretext simply masked Britain’s subjection to those sinister forces who were intent on destroying Germany and Britain in a fratricidal war, and it was anyway shown to be pure humbug when later the Russians moved in on the eastern half of Poland – and Britain did nothing.

Hitler’s Peace Path

Hess, as Hitler’s Deputy, was no newcomer to moves for peace. At the very outset of his coming to power, Hitler, in the Reichstag on 17 May 1933, had proposed general disarmament. Despite no response, he had next proposed on 4 October of that year at least some limitations on armaments. Despite no response again, he had on 21 May 1935 again proposed limitation, including the restriction of bombing to actual battle zones as preparatory to banning all bombing. Despite yet again no response, he had on 31 March 1936 put forward a peace plan including limitations on bombing and shelling. Yet again there had been no response from Britain and the other ‘democracies.’ Nevertheless, at the height of the Polish crisis Hitler, on 24 August 1939, had proposed an agreement which included a promise to help protect the British Empire. Britain, in the greatest act of folly in her history, had answered this with the commencement of a calamitous war which led to the ruin of that Empire.

Having quickly defeated the Polish stalking horse, Hitler, on 6 October 1939, had called for a peace conference, and on 9 October the German Government had said it would accept American mediation with Washington as the venue. Three days later Britain had intimated rejection. Having next defeated France and caused the British Expeditionary Force to depart from the shores of that country, Hitler, accompanied by Hess, made in the Reichstag, on 19 July 1940, what he called “an appeal once more to reason and common sense in Great Britain,” saying, “I see no reason why this war should go on,” and demanding no forfeitures from the foe for her defeat on the Continent. One hour later Sefton Delmer, in charge of German-language programmes for the BBC, had given the following answer, endorsed by the Government in Parliament:

“Mr. Hitler… let me tell you what we here in Britain think of this appeal of yours… we hurl it right back at you, right in your evil-smelling teeth.”

Churchill Wanted War

Churchill, that catastrophic conjurer of patriotic emotions for alien interests and inimical ends, had by now become Prime Minister, thanks to the war he had so long worked for as his necessary theatre for fame. When, the month after Hitler’s peace speech, he had found that 3 of the 6 members of his Cabinet were inclined to peace, he sought to scotch this untoward development by ordering an air raid on Berlin at a time when Hitler had ordered that British cities should not be bombed.

When informed in 1941 that Hess had come to Britain to make peace, this prime cause of the “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” which his war cost the British people retorted that this arrival (of a truer friend of Britain than he ever was) would not interfere with his enjoyment of a film featuring the Marx Brothers.

Thus, instead of responding sensibly to Hess’s mission, and thereby saving millions of lives, and preventing the seizure of half of Europe by Moscow, bewitched Britain, under the spell of the bloodthirsty drunkard of Downing Street, misdirected a magnificence of national spirit to the cause of killing as many of Hess’s compatriots as possible, and destroying as much of their country as possible, to the enormous delight of the foul fraternity who behind the scenes pulled the strings of political puppetry.

Hess Under Treatment

From Scotland Hess was brought South, incarcerated briefly in the Tower of London, and then taken to Mytchett Place, a requisitioned mansion near Alderson. There he was subjected to various forms of ‘treatment’ designed to extract information from him, and to mould him to the propaganda purposes of the Churchillian warmongers. This accounts for their allegations that he required ‘psychiatric observation,’ as it does for Hess’s faked loss of memory as a measure of self-protection against the interrogations, and his complaints that chemicals were being put in his food and drink; and it explains their subsequent depiction of him as ‘deranged’ when they failed to get what they wanted out of him.

As an example of the abuse of one who, if not accorded the courtesy of an ambassador of peace, at least deserved the rights of a prisoner of war under the Geneva Convention – which forbade the solitary confinement accorded to him, Hess was confronted with a faked copy of the Daily Telegraph of 20 June 1941 containing a report of an interview Hitler gave to a former U.S. Ambassador in Belgium, doctored to give the impression that Hitler had spoken of Hess as a madman. The hope was that this forgery would turn Hess against Hitler, and cause him to give away information in retaliation.

Described in the Daily Telegraph of 22 March 1971, this trick, which completely failed, was the bright idea of the same Sefton Delmer we have encountered earlier. He headed a special unit for the use of deceit in the cause of democracy, the arch-deceiver. In his memoirs, The Germans and I, he testified to the unlimited skullduggery practised by his band of ‘truth-benders,’ as they were known.

Hess’s son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess, in his new book, My Father Rudolf Hess tells of another of Delmer’s forged newspapers, this one reporting that Frau Hess had told the Berlin police that she had drugged her husband to put him under the influence of British hypnotists to cause him to come into British captivity. Delmer, having been a Fleet Street journalist, was well trained in the way in which truth can be bent in the ‘free press’ of a democracy.

Complaint To The King

Such was the maltreatment of Hess that in June 1941 he tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide, and in November 1941 he wrote these words to King George VI:

“I came to England banking on the fairness of the English people… Could I not expect all the more to be met by fairness, having come not as an enemy – especially as I came to England unarmed, at the risk of my life, to try to end the hostilities between our two peoples.”

Hess also composed a memorandum at that time, which, with prophetic insight, stated:

“A victory for England would be a victory for the Bolsheviks. A victory of the Bolsheviks would mean sooner or later their advance into Germany and the rest of Europe… If England’s desire to weaken Germany were fulfilled, the Bolshevik State would become the strongest military power on earth…”

These two items are culled from the papers of Lt. Col. A.J.B. Larcombe (disclosed in the Sunday Telegraph, 13 December 1981) who in 1945 escorted Hess to Nuremberg; for when, after four long years of further slaughter, Churchill’s blood lust was finally satisfied in the infinite misery of Germany’s unconditional surrender, Hess went home to Germany, not as an honoured peacemaker, not as a released prisoner of war, but instead as an alleged criminal – victim of vengeance, which under Churchill’s V sign, was the accompaniment of a democratic victory.

Venue Of Vengeance

Nuremberg was carefully chosen as the venue for this particular act of vengeance. Over the roofs of its medieval quarter Hitler’s plane had been wont to descend on its arrival for the gigantic processions through the streets of the city of the exultant manhood of a Germany reborn. So, with true Old Testament spite, high explosive and incendiary bombs had been generously rained down on that architectural treasure house to destroy the setting for the great spectacles of National Socialism; and so now to Nuremberg Hess and the other captured leaders were conveyed for a festival of vengeance masquerading as an exposition of justice, opening in November 1945 and extending a whole year till October 1946.

While outside the courtroom of the International Military Tribunal the gaping craters, the hillocks of rubble, and the remnants of homes all testified for Hess against his accusers, inside the place he who had sought to save Europe from all this was charged and convicted of crimes against peace and conspiracy to commit such crimes, and was sentenced to imprisonment for life. Of the other two counts in the four-count indictment against Hess, namely of war crimes and crimes against humanity, even that crooked caricature of a court had to stop short of conviction. Those proceedings at Nuremberg, which have been the sole basis for the caging of Hess for half a lifetime, were nothing less than a complete perversion of justice which, in reality, condemned not the accused but the accusers.

Under Jewish Management

“It was the World Jewish Congress which had secured the holding of the Nuremberg Trials at which it had provided expert advice and much valuable evidence,” boasted Congress spokesman Rabbi M. Perlzweig in the London Jewish Chronicle, 16 December 1949.

Members of Rabbi Perlzweig’s triumphant tribe were abundant on the staff of the Nuremberg Tribunal and its associated agencies, ranging from Col. B. C. Andrus, in charge of the emaciated prisoners kept in unheated pens under the harshest conditions and with floodlights shining on them all night, to the hangman, John C. Woods, who, on a Jewish feastday, killed with a slow-death-drop 11 of the 23 defendants, ensuring that, for example, Field Marshall Keitel took 24 minutes to die (Nuremberg: A Nation on Trial, by German historian Werner Maser). The bodies of the dead were then cremated at Munich, birthplace of National Socialism, and the ashes were dumped in the River Isar.

Hess and the others sentenced to imprisonment were then taken to the execution room and made to clean up the mess made by the deliberately prolonged murder of their colleagues.

The charges against Hess and his associates were inventions without precedent, unknown in German and other European penal codes, incompatible with the theory and usage of international law, and applied retroactively and thus contrary to all normal legal practice. They were additionally invalid because applied with perverted partiality by this victors’ tribunal whose eight judges included, along with two each from Britain, France, and the U.S.A., two from the Soviet Union, a country which had been expelled from the League of Nations for its aggression against Finland in 1939 – precisely the kind of offence for which Hess was convicted – and which, furthermore, put more people in concentration camps and exterminated more opponents than any other country in modern times. One of the Soviet pair was none other than I. Nikitchenko, who had been in charge of Stalin’s show trials.

One-Sided ‘Justice’

This Allied tribunal, however, had concern only for the alleged wrongdoings of the Germans, and none whatsoever for any comparable conduct by its own side. Thus, for example, in relation to Hess’s conviction no cognisance was taken of the British invasions of Iceland in 1940 and Syria and Iran in 1941, or Britain’s plan to invade Norway in 1940.

Commented Lt. Col. Liddell-Hart in his History of the Second World War (pages 58/59):

“One of the most questionable points of the Nuremberg Trials was that the planning and execution of aggression against Norway was put among the major charges against the Germans… Such a course was one of the most palpable cases of hypocrisy in history.”

The truth is that Germany got to know of British plans to invade Norway and thence Sweden in order, among other things, to stop the vital supply of Swedish iron ore to the German armament industry, and the Germans got into Norway to prevent this just hours ahead of the British. British Cabinet and Foreign Office papers, newly released to the Public Record Office, were shown by the Daily Telegraph of 1 January 1971 to disclose that, as far back as December 1939, Britain and France plotted to send regular troops, in the guise of volunteers to aid Finland against Russian aggression, but with the real aim of stopping the Swedish supplies of ore to Germany. This particular violation of neutrality was prevented by the Swedish refusal to signify sanction for the transit of the bogus ‘defenders of Finland’ across Swedish territory, but it did not stop Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, continuing to scheme to the same end, and to dispatch an invasion force to Norway which was beaten to its destination by the German counter-move.

Allied Atrocities Condoned

While Hess was charged unsuccessfully, and others successfully, with crimes of war and crimes against humanity, the atrocities of the Allies were treated as inadmissible as evidence by their judicial hirelings at Nuremberg. Yet former tank major Desmond Flower, MC, then Deputy Chairman of publishers Cassell & Co., was quoted in the Sunday Dispatch of London on 15 April 1956 as stating that during the invasion of Europe British soldiers shot prisoners of war and civilians, and looted and wantonly destroyed civilian property; and more recently, Max Hastings in his Operation Overloard recorded that the shooting of German prisoners was a common Allied practice.

The defence was barred from mentioning such shootings, and from introducing the British Army Manual of Irregular Warfare, which advocated the same activity the defendants were charged with and punished for. Similarly, the defence was barred from citing the deliberate mass slaughter of German civilians at Dresden, Hamburg, and elsewhere in Germany by the British and American bombing raids. Summarising the disqualifying double-standard demonstrated by the tribunal, even Robert H. Jackson, the chief American prosecutor, admitted in a letter to the then President Truman:

“The Allies have done or are doing the very same things we are prosecuting the Germans for.” (Justice at Nuremberg, Robert E. Conot, p. 68).

Handicapped Defence

Not only were the purview and composition of the tribunal a travesty of justice, so too were its ways and means. The London Agreement which set it up laid down that its constitutionality could not be challenged. Its Article 19 decreed that “The Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence” – so that it could dispense with the normal safeguards against injustice. Article 21 of the same document decreed that “The Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge” – so that it could treat as unquestionable contentions advantageous to the prosecution.

Defense staff had to work in a dimly lit room under constant surveillance by American military police, faced continual obstruction in collecting evidence, and were not allowed to see prosecution material before its submission. Werner Maser, above cited, showed that among other measures designed to pervert justice prosecution witnesses were beaten until they gave the desired ‘evidence,’ many defence witnesses were not allowed to appear, agreements to advise the defence of topics to be examined the next day were not kept, the defence was not allowed to have copies of many prosecution documents of evidence, defence documents had to be sifted by the prosecution before they could be submitted, and many of these documents were confiscated or stolen.

Hess was not allowed to conduct his own defence, despite provision in the tribunal’s charter, and, when he sought to exercise his right to make a closing statement, he was cut short with the ruling that he must be brief.

Prosecution Forgeries

Falsified material was used by the prosecution to secure the convictions of Hess and the others. The private file of the chief American prosecutor revealed that newsreels shown as evidence were doctored by his staff (David Irving, The War Path).

Allied prosecution exhibit USSR-378 was the book by Herman Rauschning, Hitler Speaks, purporting to be Hitler’s most intimate views and plans as revealed through a great many private conversations with the author, including the intention to incorporate Africa, South America, and eventually the U.S.A. in a global empire, and the statement, “Do I propose to exterminate entire nationalities? Yes, it will add up to that…” Swiss historian Wolfgang Haenal, after 5 years’ investigation, has revealed that this almost unknown provincial official only met Hitler four times and never alone, and the material is pure fiction. The German magazine Der Spiegel, 7 September 1985, called it “a falsification, an historical distortion from the first to the last page…”

Another falsification was prosecution exhibit 386-PS, the Hossbach Protocol, used to prove that Hitler planned aggressive war, and thus that Hess, as his Deputy, was culpably a party to it. West Berlin lawyer, Dankwart Kluge, has shown in a book published in 1980 that the Allied authorities got hold of a copy someone else made of a note made by a Col. Hossbach of the proceedings of a conference with Hitler that he and others attended in 1937, and substantially altered it. In his eventual memoirs Hossbach admitted that Hitler did not outline any war plan at the conference, and British historian A.J.P. Taylor (An Old Man’s Diary, 1984), rejecting the Nuremberg exhibit as a forgery, said: “No evidence that Hitler planned an aggressive war has ever been produced.” Thus Hess’s conviction was counterfeit.

Hess’s Birthday

Forty years after the Nuremberg festival of vengeance, the pale light of the early morning brought to sight the bare furnishings – bed, table, and chair – of a small barred room in Spandau Prison, West Berlin, where on 26 April 1986 Rudolf Hess reached his 92nd birthday, and at 6 a.m. the guard obliged him to rise. There were no birthday cards from the public to greet the old man, for these, Christmas cards and all other mail, are denied him, apart from a single letter per week to and from his family.

He may have a visit from his wife or son for a single hour each month, but needs to remember the rule to keep two full yards away from his loved one. Never must he touch his visitor. With that visitor will also attend the British, French, American, and Russian prison commandants, and, for the benefit of the latter, every word uttered will be loudly translated into Russian, so the prisoner must always remember to speak slowly.

Hess spent his birthday trying to read the four newspapers he is allowed daily, and one of the four books he is allowed monthly; a difficult matter despite the combination of spectacles and a magnifying glass because he is now blind in one eye and has a detached retina in the other one which is inoperable because of his age, and increasingly reduces his sight; so he must make the most of his remaining time before total darkness is added to his imprisonment. His reading matter must exclude anything relating to his case, his past, or National Socialist Germany in general, and any notes he makes are taken away and destroyed.

For him to watch television, a concession now allowed him but similarly censored, he needs to apply a week in advance, specifying the desired programme. News bulletins and programmes of contemporary history are not allowed.

Weather permitting – and despite oedema of the legs and a weakness in the thigh bones which causes his knee joints to give way so that he falls and cannot get up unaided – he could go down to shuffle around the exercise ground, where he has already walked the equivalent of three times around the world, or to tend the garden plot which gives him pleasure. While so doing he could cast a glance in the direction of the prison basement where already his coffin stands waiting for him, destined for immediate cremation, his ashes to be denied to his family, and disposed of secretly.

Spandau’s Secrecy

The four custodial powers maintain to this day a secrecy concerning Hess’s prison conditions and the state of his health which can only be seen as a cloak for culpability. Thus the British Foreign Office replied on 5 March 1985:

“Mr. Jordan asks five specific questions in his letter. I regret that I cannot supply him with specific answers on the conditions of Hess’s imprisonment. The Spandau Prison regulations are confidential. The consent of the Four Powers, including the Russians, would be needed for their publication. The same applies to details of Hess’s medical condition.”

When on Hess’s 92nd birthday this writer asked the British Foreign Secretary if he would mark the occasion by asking the other three powers to end this secrecy – and at the same time to agree to end restrictions on Hess’s mail, reading, and television – the reply was: “It is not possible, in Hess’s own interests, to give details of Allied proposals.” Thus secrecy concerning secrecy is the name of their game.

A fortnight following our last look at Spandau’s solitary prisoner, it was 10 May 1986, and the 45th anniversary of his flight to Britain. Even after more than 16,000 days of imprisonment he can still sharply remember his feeling as the plane left German soil at Augsburg around 5.45 p.m. When his feet next touched ground a few hours later in Lanarkshire, it was to start nearly half a century of captivity.

Letter To Thatcher

On the same anniversary in 1986 this writer yet again tackled the British Government regarding the release of Rudolf Hess, writing the following letter to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, which so far has only received bare acknowledgement:

“I write to you this day, the 10th May, the anniversary of Rudolf Hess’s flight to Britain in 1941, and thus the completion of 45 years of his imprisonment, to ask if you will mark this occasion by making another approach now to the Soviet Union to agree to the release of this very old and partly blind prisoner whose 92nd birthday took place a fortnight ago.

“I appreciate that the British Government maintains that it has made a number of such approaches over the past years without success, but I do put it to you that Britain has a special responsibility in the matter in that Hess first lost his liberty in consequence of his endeavour to make peace between our country and his through a singularly courageous feat of flying. I therefore submit that it will be shameful for Britain, if she fails now, while there is still time, to urge in the strongest possible way the Soviet Union – which she contents is the only one of the four custodial powers objecting – to agree to Hess’s immediate release, and instead wait and allow the problem to be removed by his death which cannot be far off.

“In conjunction with this, I wish here to ask you to reconsider the British Government’s present decision to keep its papers on Rudolf Hess secret till the year of 2017, and instead authorise public access to those papers as a gesture of good faith in accord with its claim to favour Hess’s release; since otherwise the maintenance of this secrecy can but give rise to the belief that the Government has something damaging to hide by this secrecy.”

Britain’s Excuses

The British Government maintains the pose that, while favouring the release of Hess, it cannot during one of the months when, in rotation with other powers, it has control of Spandau, either free him, or in lieu place him in some other and more comfortable custody, because this would be to break an agreement with the Russians which would be immoral, and also inexpedient in jeopardising to our detriment other agreements with them. This argument is unconvincing. Firstly, it is morally preferable to break a wrongful agreement than to continue it – and Hess’s continued imprisonment at his age and after so many years on account of a wrongful conviction at Nuremberg is beyond question monstrously wrongful – while the Russians, on account of the number of agreements they have broken at their convenience, including, according to the Washington Enquirer (21 September 1984), 17 arms control commitments between 1958 and 1983, are hardly entitled to invoke integrity in their favour.

Secondly, the Russians, being by doctrine and practice devoted to keeping agreements only if and as along they suit their purposes, would not be likely to let their huffing and puffing over the release of Hess without their approval ultimately interfere with their disposition concerning other agreements. One is therefore led by this reasoning to view the British Government’s decision to keep its Hess papers secret till 2017 – and thus till after not only Hess is dead, but almost everyone else who was an adult at the time of his flight – as a powerful clue to false pretences on its part. Indeed this writer believes, not only that those papers are likely to show something of potentiality for peace still prevailing in Britain in 1941 as a response to Hess’s mission, which Churchill and his cronies were intent on suppressing in their lust for war, but also the fact that, just as Hitler only narrowly forestalled by hours Churchill’s plan to violate Scandinavian neutrality in 1940, so too a year later he only narrowly forestalled by days Stalin’s plan to launch a surprise attack on Germany in violation of the pact between them.

Hess Silenced

Did not Hess – aware from German intelligence of the Russian preparations to attack then proceeding, necessitating the swift German counterattack then being planned – time his flight when he did in the knowledge that the great struggle for Europe against Bolshevism was about to begin, a struggle in which Britain should not figure on the side of the latter?

Did not Churchill realise that this was his chance to destroy, with the help of Stalin’s hordes, the hated champion of European Civilisation, and thus to realise his consuming ambition to strut across the pages of history as a conquering warlord? Had he not already conspired with Stalin to this end in his approaches starting in 1940, just as he had conspired with the Czechs and taken their bribes in 1938 to help bring the war about (David Irving: The War Path, p. 136), and had conspired with Roosevelt to bring America into it, as coding clerk Tyler Kent discovered – later being silenced by imprisonment?

Did not Churchill determine to silence Hess by confinement, and have not successive British Governments kept the Hess papers secret, and in league with their wartime allies kept Hess imprisoned, precisely because this prisoner of peace knows too much and could tell too much, destroying their fictions of rectitude, and thereby exposing their crime in detaining him?

Are they not, one and all, despite their pretences, determined to keep Hess caged in Spandau until the day death silences him forever – because, if freed and free to talk, he would as a result be acquitted by all fair opinion, while Churchill would be condemned and the conception of his ‘just’ war against Germany would collapse? Democracy’s misrulers could not withstand the damage thus done to the very foundations of their essential edifice of lies.

His Victory

Within the prison walls of Spandau the subject of our speculation will tonight have his spectacles removed at 10 p.m. lest his fumbling fingers beneath the bedclothes manage to break the glass, and use it to end his torment prematurely. Throughout the drab procession of days and nights across the dreary decades his sustaining strength has been the satisfaction of knowing that, despite everything, he has beaten them because he has kept faith. As against all uncertainties concerning him stands the certainty of his steadfastness. Had he been a mere fellow traveler, like technocrat Speer, or some lesser believer or weaker character, he could perhaps have bought his release by penitential recantation, plus an undertaking to be silent on what his captors desire to be kept secret. Democracy and its cousin Communism would dearly love to release and parade a beaten and repentant Hess, as a token of their ‘compassion,’ and have him recite all their proclaimed evils of National Socalism.

But they are doomed to disappointment. He who uttered the following words of defiance to the judicial vultures of Nuremberg amid the ruins of Aryan renaissance will never give in, and, in his triumph of the will, holds high a torch of honour to the remembrance, redemption, and revival of that renaissance:

“It has been my privilege to serve for many years under the greatest son to whom my people has given birth in its thousand years of history… If I were to begin all over again, I would act just as I have acted, even if I knew that in the end I would meet a fiery death at the stake.”

Stünde ich wieder am Anfang,

würde ich wieder handeln

wie ich handelte.

Auch wenn ich wüßte,

daß am Ende

ein Scheiterhaufen für

meinen Flammentod brennt.

Gleichgültig was Menschen tun,

dereinst stehe ich vor dem

Richterstuhl des Ewigen.

Ihm werde ich

mich verantworten,

und ich weiß:

Er spricht mich frei!

Schlußworte von Rudolf Hess

Stellvertreter des Führers

vor dem Nürnbenger Tribunal, 1946

[This article first appeared in Liberty Bell, January 1987 (vol. 14, no. 5), pages 47-60. A PDF of this issue can be downloaded here. It later appeared in National Socialism: Vanguard of the Future (Selected Writings of Colin Jordan), Nordland Forlag, Aalborg, 1993. Pages 51-66.]